United Kingdom [1917]

By Ayesh Perera, Last Updated: June 03, 2021

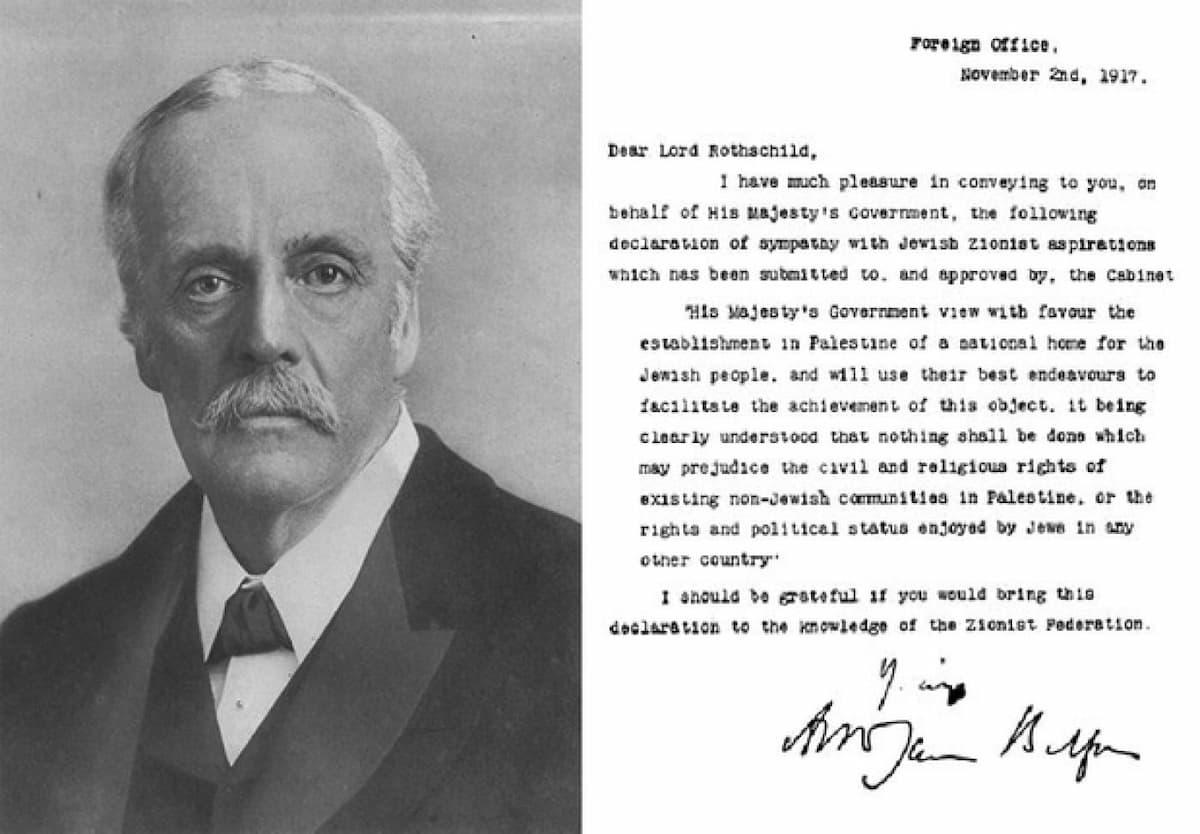

Signed: 2 November 1917

Location: British Library

Author(s): Walter Rothschild • Arthur Balfour • Leo Amery • Lord Milner

Signatories: Arthur James Balfour

The Balfour Declaration is a statement issued in 1917, amidst World War II, by the British government, publicly announcing its support for the reconstitution of a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people.

The statement was in a letter sent by Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, to Lionel Walter Rothschild, a prominent member of the British Jewish community.

Dated November 2nd, 1917, the letter was to be transmitted to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the letter was published on the 9th of November 1917.

Secretary Balfour’s letter was preceded by multiple efforts by various British individuals and groups to establish a home for the Jewish people in ancient Israel.

Led by Lord Palmerston in the 1840s, there were efforts to expand the span of British influence in the Middle East. While the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox communities in the region had helped the growth of French and Russian influence, the British were still in need of a ‘protégé’ community to channel their power through.

These geopolitical considerations found a ready companion in certain theological aspects of Evangelical Christianity. Not a few Evangelicals believed that the return of the Jewish people to the land of their forefathers would be a fulfillment of prophecy.

Among such Christians were British political elites such as Lord Shaftesbury. Soon, the British Foreign Office was actively encouraging the emigration of Jews to Palestine, and prominent figures such as Charles Henry Churchill, the British Consul in Ottoman Syria and Sir Moses Montefiore, the head of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, would begin strategizing for the establishment a Jewish state.

All of this was occurring as early as the 1840s, nearly half-a-century prior to the birth of official Zionism.

The rise of exclusionary nationalist movements in Eastern and Central Europe, the pogroms in Russia, and the Dreyfus affair convinced many Jews that permanent safety for Jews in Europe is a futile hope.

These regular manifestations of anti-Semitism helped gain the support of many Jews for the formation of Hovevei Zion organizations in 1881. Led by Leon Pinsker, these organizations actively encouraged immigration to Palestine.

These Zionist efforts, however, would soon be thrust into high gear in 1897 with the establishment of the Zionist Organization (later known as the World Zionist Organization) by Theodor Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism.

With its unabashedly explicit mission to establish “for the Jewish people a legally assured home in Palestine,” it soon started strengthening Jewish consciousness within the diaspora and promoting Jewish settlements in Palestine.

The plan also included the obtainment of the essential governmental grants for the eventual establishment of the State of Israel. Herzl died in July 1904. However, his dream did not.

Around this time, Chaim Weizmann, who would later become the President of the World Zionist Organization, would move from Switzerland to the United Kingdom and meet Arthur Balfour, who would later author the Balfour Declaration.

Weizmann’s meeting with Balfour, who had just launched his campaign for the 1906 election, was arranged by Charles Dreyfus, the representative of Balfour’s Jewish constituency. During the meeting, Balfour inquired of Weizmann as to why he had opposed the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Uganda; the Uganda scheme had been rejected by the Zionist Organization following Herzl’s death.

Weizmann shot back with a question: “Mr. Balfour, supposing I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?” “But Dr. Weizmann, we have London,” responded Balfour. “That is true,” acknowledged Weizmann, and then added “but we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.”

That Weizmann would accept nothing less than Palestine was evident. However, much work had to be done before his hopes would materialize. In 1914, Weizmann would meet Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a leading advocate of Zionism.

He was also a member of the French side of the Rothschild family. This connection would prove crucial.

Later, through his daughter-in-law, Dorothy Mathilde de Rothschild, he would be introduced to the English branch of the Rothschild family, in particular, to Lionel Walter Rothschild who would become the official recipient of the Balfour Declaration.

As war broke out among major European powers in July 1914, the future of the Zionist project, for a while, seemed uncertain. However, Britain declared war against the Ottoman Empire on the 5th of November 1914.

The Ottoman Empire had ruled Palestine for centuries. Now, a British victory in World War I, Weizmann realized, could determine the destiny of Palestine, and that of his people.

On the 10th of December 1914, Weizmann would meet Herbert Samuel, a secular Jew and a member of the British Cabinet, and discuss the Zionist project. To Weizmann’s pleasant surprise, Samuel’s plans were more audacious.

Samuel related that the Jews should build harbors, railways, a network of schools and a university in Palestine. He also hoped that the Temple too, could be rebuilt as a symbol of Jewish unity.

In January 1915, a month later, Samuel would circulate a memorandum titled “The Future of Palestine” to the British Cabinet. In it, he wrote that “the solution of the problem of Palestine […] would be the annexation of the country to the British Empire.”

Samuel also discussed his memorandum with Lord Nathan Rothschild, the father of Lionel Walter Rothschild, the recipient of the Balfour Declaration, as well as with Lloyd George, presently the Minister of Munitions, and later the Prime Minister Britain.

In the meantime, the British war effort was faced with a major problem: a shortage of acetone which is used for the production of cordite (the propellant for artillery shells) and of fire-resistant lacquers (for the wings of military aircraft). Germany and Austria, wherefrom Britain had previously imported acetone, were now on the opposing side.

Moreover, the American acetone market had become exceedingly fragile. As the Minister of Munitions, Lloyd George had to find a way to solve the issue. After hearing from C.P. Scott, the Editor of the Manchester Guardian, that Professor Chaim Weizmann might be capable of devising a solution to the problem, George would invite Weizmann to London to discuss the issue.

Weizmann informed him that producing acetone via a fermentation process is possible. However, more time was needed to ascertain whether it could be done on a manufacturing scale. Few weeks later Weizmann returned and assured George that he had solved the problem and that Britain, indeed, would be able to manufacture acetone on a large scale.

As a scientific advisor to the Ministry of Munitions, Weizmann would go on to render an invaluable service to the British war effort. Grateful for Weizmann’s genius, George said to him: “You have rendered a great service to the State, and I should like to ask the Prime Minister to recommend you to His Majesty for some honour.” Weizmann responded: “there is nothing I want for myself.”

But he added: “I would like you to do something for my people.” Weizmann would, then, relate his aspirations concerning the repatriation of the Jews to Palestine. Later, in his War Memoirs Lloyd George would note that this was “the fount and origin of the famous declaration about the National Home for the Jews in Palestine.”

George would recall: “As soon as I became Prime Minister, I talked the whole matter over with Mr. Balfour, who was then Foreign Secretary.” George would further reflect that “Dr. Weizmann was brought into direct contact with the Foreign Secretary” and that “this was the beginning of an association, the outcome of which, after long examination, was the famous Balfour Declaration.”

Whether or not Weizmann’s contribution to the British war effort was actually the primary cause of the Balfour Declaration, the impact of these events on the British policy toward Palestine cannot be gainsaid.

It must also be noted that as the New York Times’s Tom Segev points out, Lloyd George and Balfour were “deeply religious Christian Zionists” who believed that the Zionist project would “fulfill a divine promise and resettle the Jews in the land of their ancient fathers.”

In other words, it was likely that both George and Balfour had reasons beside the pressure of Zionist Jews to support the return of the Jews to Palestine.

In December 1916, Britain saw a transition of power to a new coalition government under Lloyd George. Prime Minister George as well as his Foreign Secretary Balfour, saw the partition of the Ottoman Empire as a crucial British war objective.

Two days after taking office, Prime Minister George informed General William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, that he desired a major victory, preferably including the liberation of Jerusalem.

This plan soon led to the capture of Sinai, El Arish and Rafah by the spring of 1917. These victories, however, were followed by a long stalemate in Southern Palestine until October. Nonetheless, with the imminent possibility of the liberation of Jerusalem by the British, the Zionist efforts to lay the initial legal foundation for a Jewish state gained a surge of momentum.

On the 22nd of March 1917, Weizmann met Balfour at the Foreign Office and explained to him that the Zionists preferred a British protectorate over Palestine to a French, American or international arrangement.

Balfour understood Weizmann’s concerns, but pointed out that there would be challenges with Italy and France. In the meantime, another Zionist leader, Nahum Sokolow, would work diligently to secure the support of the French and Italian governments and the Vatican for the Zionist project.

Sokolow’s diplomatic feats would prove to be crucial in Britain’s final decision to issue the Balfour declaration.

By June 1917, the three most important individuals, the British Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary and the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, were all in support of establishing a national home for the Jews in Palestine.

On the 19th of June, Balfour would ask Weizmann and Lord Rothschild to present a formula for the declaration. Within weeks, the Zionist negotiating committee produced a 143-word draft. However, this was considered to be too specific in relation to sensitive matters.

Another draft was produced by the Foreign Office. This draft mentioned a “sanctuary for Jewish victims of persecution.” The Zionists strongly opposed the draft, and it was discarded. More debate and discussion ensued concerning the most appropriate wording for the declaration.

Lord Miler, a Cabinet member, wanted the scope of the land for the Jewish state reduced from the entirety of Palestine to a land ‘in Palestine.’ Moreover, both Lord Milner and the war cabinet secretary, Leopold Amery, argued for the addition of the two safeguard clauses concerning non-Jews in Palestine and Jews outside Palestine.

Finally, following much alteration, Lord Rothschild sent a brief draft to Balfour on the 18th of July. This draft was accepted by the Foreign Office and was presented to the Cabinet for consideration.

In the War Cabinet, four formal meetings were held concerning the final draft. The opinions of government ministers, Zionist as well as non-Zionist Jews, and notable war allies, such as the American President Woodrow Wilson, were considered.

Finally, on the 31st of October 1917, the British War Cabinet formally decided to issue the declaration. The finalized declaration was dispatched on the 2nd of November 1917, to be transmitted to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, in a letter from Balfour to Rothschild.

Containing only a single sentence of 67 words, the Balfour declaration read as follows:

“His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

The choice of Lord Rothschild as the official recipient of the declaration was far from arbitrary.

In addition to being a prominent leader of the Zionist movement, Lord Rothschild was also a military veteran, a wealthy banker, a famous statesman and a well-known zoologist. In brief, he was the nation’s most illustrious Jew, and probably the most influential leader of the British Jewish community.

The decision to address him, obviously, was not without far reaching consequences.

About this time, the British forces broke through their stalemate in Southern Palestine. The British advanced triumphantly gaining victory after victory in the battles of Beersheba, Tel el Khuweilfe, Hareira and Sheria, and Mughar Ridge.

Finally, “the Hanukkah Miracle” happened on the morning of December 9th, 1917. As the vanquished Turkish troops fled the region of Jerusalem after a single day’s fighting, the British General Edmund Allenby dismounted his horse and entered the Holy City on foot.

The mayor of Jerusalem handed the keys of the city to General Allenby who would become the first Christian to rule over Jerusalem after nearly four centuries. Church bells rang from Rome to London to celebrate the victory.

Prime Minister Lloyd George hailed the liberation of Jerusalem as “a Christmas present for the British people.” Now, the ancient home of the Jews was entirely in British hands, and the Balfour Declaration, before long, would be at the center of attention.

The use of the term ‘national home’ instead of ‘state,’ which would have been more legally binding, constituted a fertile source of questions and controversy.

On one hand, the declaration, consequently, was not a legal guarantee for an independent Jewish republic. On the other hand, however, the use of the term ‘home’ obliged the British government to acknowledge the right of Jews to migrate to their ancient home.

In other words, the declaration did promise the Jewish people that they could settle in Palestine. Moreover, despite the seeming ambiguity, the declaration was tacitly construed as a necessary initial step toward the establishment of a Jewish State.

Nearly, a month after the Balfour Declaration was issued, the deputy Foreign Secretary Lord Robert Cecil would assure the English Zionist Federation: “Arabian countries shall be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians and Judea for the Jews.”

The following year, Neville Chamberlain would express his support for a “new Jewish State” while chairing a Zionist meeting. Later, Winston Churchill too would state that it would be beneficial to have “in our own lifetime, by the banks of the Jordan, a Jewish State under the protection of the British Crown, which might comprise three or four millions of Jews.”

Additionally, France would issue a statement in February 1919, indicating that it would not oppose the formation of a Jewish State, and Greece’s Foreign Minister would state that “the establishment of a Jewish State meets in Greece with full and sincere sympathy.”

In Switzerland, the formation of a Jewish state was construed to be a sacred right of the Jews while in Germany, many understood the Balfour Declaration to assure a Jewish State sponsored by the British.

While it is true that the Balfour Declaration was not a legally binding assurance to create a Jewish State, many saw it as a prelude to establishing the future nation of Israel.

Despite the sanguine acceptance of the declaration by many, not everyone embraced it. Arabs and non-Zionist Jews, though for different reasons, constituted the major groups which felt prejudiced by the Balfour Declaration.

For instance, a delegation of the Muslim-Christian Association, led by Musa al-Husayni, the Mayor of Jerusalem, publicly disapproved of the formation of a Jewish state.

Moreover, the Sharif of Mecca accused the British of violating their commitment to the Arabs in the previous McMahon-Hussein correspondence, in which Britain had promised to eventually acknowledge Arab independence in exchange for the Arab revolt against the Turkish Empire.

Moreover, as a result of the Balfour Declaration, King Hussein refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, and later said that he would not “affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists.” The dangers which the declaration would create for Jews outside Palestine were not insignificant.

Few months prior to the official release of the Balfour Declaration, Claude Montefiore, the President of the Anglo-Jewish Association , and David Lindo Alexander, the President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, had jointly released a statement in which they argued that the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine will, “have the effect throughout the world of stamping the Jews as strangers in their native lands,” and will undermine “their hard-won position as citizens and nationals of these lands.”

Furthermore, Edwin Montagu, the Secretary of State for India and an anti-Zionist Jew, would argue that the support for a Jewish national home in Palestine “will prove a rallying ground for anti-Semites in every country of the world.”

The persecution and the subsequent massive exodus of Jews, from predominantly Muslim countries ranging from Bahrain to Bangladesh in more recent years, demonstrate that the abovementioned statements were not empty warnings.

Many see two main outcomes as the primary results of the Balfour Declaration: the emergence of Israel and the ongoing Israeli-Arab conflict. The rise of religious Zionism would soon exponentially expand the Zionist movement.

Jews from around the world would start making aliya and pouring into Palestine. In the meantime, beginning in 1920s’ Jaffa riots, the conflict between Jews and Arabs would escalate.

The intercommunal violence would never cease. The official birth of the Jewish State of Israel would, in fact, turn the situation into full blown war between Israel and the Arab states. Despite the manifold subsequent efforts to achieve peace in the region, the tension between the Arabs and the Israelis, to this day, remains palpable.

While to many Arabs the Balfour Declaration is the root of all evils, to millions of Jews worldwide the document embodies a monumental milestone in the restoration of Israel, the home of their ancient fathers.

The Balfour Declaration, November 1917 - Balfour Project

Perera, A.. "History of the Balfour Declaration." World History Blog, June 03, 2021. https://www.worldhistoryblog.com/balfour-declaration.html.

Ayesh Perera recently graduated from Harvard University, where he studied politics, ethics and religion. He is presently conducting research in neuroscience and peak performance as an intern for the Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies, while also working on a book of his own on constitutional law and legal interpretation.